The Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul in the United States and five other congregations of Sisters trace their early roots back to the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s in Emmitsburg, Maryland. Recently, the Federation of Sisters that includes these original six congregations (Setonian congregations) plus, in solidarity, nine additional congregations (Vincentian congregations) shared a letter with their members about the early Sisters involvement in slavery. We share that letter with you, our friends, today.

Slavery is an indelible stain on our nation’s history and conscience that has permanent and painful repercussions, most profoundly for Black Americans. As you may know, in an effort to better understand any involvement by early members of the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s, beginning in 2019 we undertook an exploration of the available historical record on this important issue. We believe that only by shining a light on difficult, shared truths can we truly move forward together in unity.

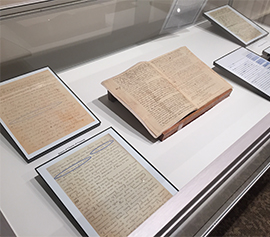

This work consisted of a thorough fact-gathering process led by the archivist for the Daughters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Maryland, involving the analysis of several historical archives within our own congregations, dioceses, and public records.

This further examination, supporting previous research on this topic, confirms that the original Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s, beginning with their founding by Elizabeth Ann Seton in 1809, and their successors, had some involvement with slavery until its cessation in the United States in 1865.

The archived records and documents reviewed to date show that, prior to 1865, the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s and the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul in the United States benefited from the labor of enslaved people in Emmitsburg, Maryland; New Orleans, Louisiana; and St. Louis, Missouri:

- The research confirmed previously reported findings of at least two enslaved individuals who were owned by the Sisters and Daughters in Maryland in 1839, and found documentation of one additional enslaved individual in 1859. These recently reviewed archival documents also indicate that Sisters received proceeds from the sale of enslaved people on at least two occasions, and that the Sisters benefited from the labor of people who were enslaved when the Sisters supervised the washroom for the Sulpician Fathers at Mount St. Mary’s.

- Further, evidence exists that the Sisters in New Orleans benefitted from the labor of enslaved individuals in the work of Charity Hospital. Although these enslaved individuals were owned by the State of Louisiana, there is some evidence that the Sisters were involved in decisions related to the sale of enslaved people in 1848.

- Finally, in St. Louis, there is documentation of at least one instance of the Sisters benefiting from labor by an enslaved person in the work of Mullanphy Hospital from December 1830 through December 1831.

This latest research also touched on the life of Elizabeth Ann Seton (1774-1821), finding no new evidence that Mother Seton owned an enslaved person. It confirmed some previously known instances of involvement with slavery during her lifetime. In 1777, her grandfather, the Rev. Richard Charlton, bequeathed then 3-year-old Elizabeth an enslaved person named Brennus in his will. There is no further record of this enslaved man’s fate, and researchers, including Dr. Catherine O’Donnell, author of the 2018 book, “Elizabeth Seton: American Saint,” believe that Brennus may have escaped during the American Revolution. In 1819, less than two years before Mother Seton’s death, financial records indicate that one of the schools she founded in Maryland knowingly accepted payment for tuition that used proceeds from the sale of an enslaved person.

The Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s were founded by Mother Seton in the state of Maryland, where the labor of enslaved persons was fully integrated and foundational. Yet, while the institution of slavery and the exploitation of enslaved people was deeply engrained in the society and economy of the 19th century, this shameful historical reality does not diminish our profound regret and dismay today.

We, who follow in the footsteps of the original Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s and the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul in the United States, apologize and ask for forgiveness.

The damage done by slavery is enduring. The passage of time does not diminish the injustices perpetrated against enslaved individuals and families or the persistent racism, discrimination, injustice, and inequity that demand continued action by all of us.

As a first acknowledgement of this chapter in our history, and a symbol of our deep sorrow and remorse, a monument to those who were enslaved will be erected on the grounds of the original Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s congregation in Emmitsburg. Going forward, we will explore additional, meaningful, actions that will contribute to the work that must be done to bring about significant change. We pledge to move further into the work of racial equity; to remember and learn from our past; and to confront systemic racism through our words and actions.

In the interest of transparency, we are sharing this letter and Q&A with others close to the Federation in the coming days, and are asking congregation leaders to share it with their congregational constituents. The material will be made available as well on the public portion of the Sisters of Charity Federation web site.

The historical fact-finding effort that we have undertaken was an important step in understanding and acknowledging our history. Like any exploration of history, however, it is by no means definitive. Our research will continue, in the spirit of continued discussion and exploration. By seeking a more complete understanding of the Sisters’ and Daughters’ past, we hope to contribute to the work that must be done to truly heal and live out our mission to right, in great ways and small, the injustices we see around us.

Our gratitude goes to all who have been, and will be, part of this work.

Click here to download a PDF of the letter.